The journey chronicled in “Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek” begins when Mrs. Eva Skinner explains that the destruction of the community cemetery where her young son was buried happened because no one was there to stop it — developers bulldozed family plots to make way for a parking lot and new housing.

The film tells the story of the community that stepped up to protect the people and place of Turkey Creek.

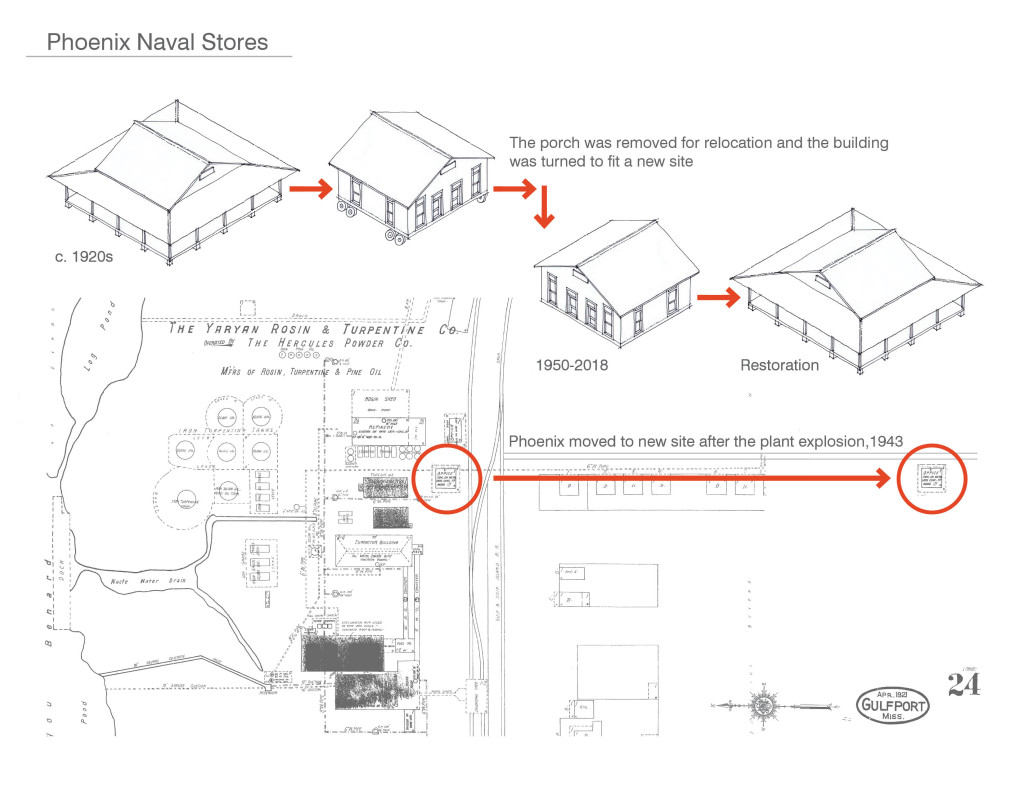

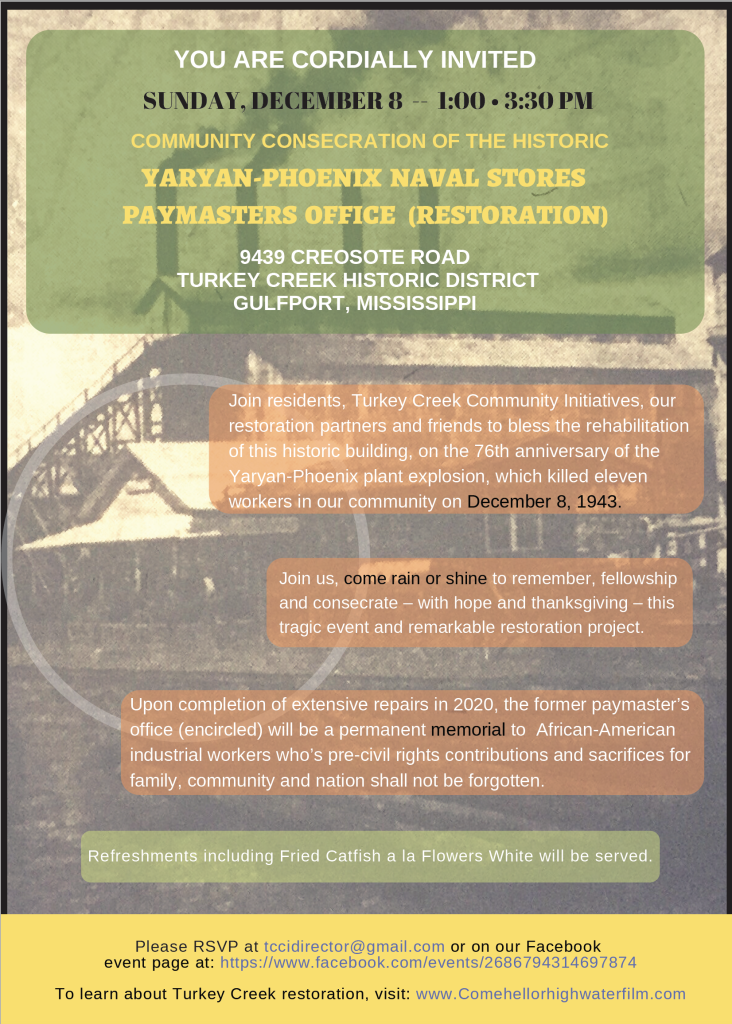

Eva Skinner’s life was also tied by tragedy — and her resilience — to the site of the historic “Yaryan” company store that will be consecrated this Sunday and restored in the coming months with a grant from the National Park Service aimed at preserving sites that “highlight stories related to the African American struggle for equality in the 20th century.” The building is the only structure remaining after a 1943 explosion at the Pheonix Naval Stores plant that killed her husband Lee Skinner and ten other workers. In the days that followed, Mrs. Skinner doubted her capacity to continue living, but she went on to raise her children on her own. She shared some of this history with filmmaker Leah Mahan, and when she died in 2014 Leah wrote a remembrance on Bridge The Gulf: “One story that is vivid in my mind is how Miss Eva supported her nine children as a single mother in the 1940s and ’50s. For thirteen years, she worked a day job doing laundry in Gulfport and a night job at a hotel in Biloxi. When her job in Biloxi was finished at 2 a.m., she walked home to Gulfport, more than twelve miles, where a neighbor was watching her children.”

On Dec. 8, the 76th anniversary of the tragedy, community members will memorialize the lives lost and the overlooked history of African American workers in the American South. Derrick Evans says that the restored Yaryan-Pheonix Naval Stores building will pay tribute to the legacies of men like Lee Skinner and his family, who were “subjected to the dangerous conditions, low wages, frequent tragedies, and social invisibilities that plagued African-American forest industry laborers in Turkey Creek and the larger Gulf Coast during the Jim Crow era.”

In 2003 Evans bought the Yaryan building to save it from demolition, and in a recent note to friends of the restoration project he explained that it was Eva Skinner who taught him much about Turkey Creek and the industry that took her husband’s life:

“Miss Eva passed away five years ago, around the same time that the City of Gulfport ordered me to demolish the building in 21 days. Severely short on energy and financial resources, I almost did just that, but instead I opted for an uphill path towards structural restoration with Judy Steckler (of the Land Trust for the Mississippi Coastal Plain) and others, mainly because of Mrs. Eva Skinner’s inspiring legacy of loss, perseverance and triumph. I could not let her and her family’s story be erased with the building from collective public memory.”

The Facebook event page for the consecration on Dec. 8 is here.

The Land Trust for the Mississippi Coastal Plain will oversee the restoration the Yaryan-Pheonix Naval Stores Office, one of the last vestiges of a thriving timber industry on the coast which employed many African Americans. The building was named one of Mississippi’s “10 Most Endangered Historical Places” by the Mississippi Heritage Trust in 2015. Derrick Evans explains that the Yaryan is a “rare and important exemplar of early and mid-20th century Southern industry” that holds important lessons about resources, labor and race. To learn more about the site, explore the lesson plan created for 5th graders.